The superhuman dilemma

Bridging the gap between your team and your users

As I churn out posts on this blog, I’m going to be using two important terms that I should probably define early on: human and superhuman. So it’s a good idea to define those now, and explain why I use them the way I do.

Also, I’ll be using some screenshots here from a talk I just gave, since I’ve already got them on hand, and if game design’s taught me one lesson, it’s that everything should be used at least twice.

In a recent talk I gave for my local UX user group, CHIFOO, I stressed the importance of using human-friendly messaging in everything we create, from digital products to physical experiences and everything in between. And in my talk, I focused on a concept that’s very close to my heart as a designer: that people close to a particular system, who understand its inner workings and what goes into making it do what it does, aren’t equipped to decide what its various parts and affordances should be called.

Because those people, according to my own incredibly unscientific terminology, aren’t humans.

In a recent talk I gave for my local UX user group, CHIFOO, I stressed the importance of using human-friendly messaging in everything we create, from digital products to physical experiences and everything in between. And in my talk, I focused on a concept that’s very close to my heart as a designer: that people close to a particular system, who understand its inner workings and what goes into making it do what it does, aren’t equipped to decide what its various parts and affordances should be called.

Because those people, according to my own incredibly unscientific terminology, aren’t humans.

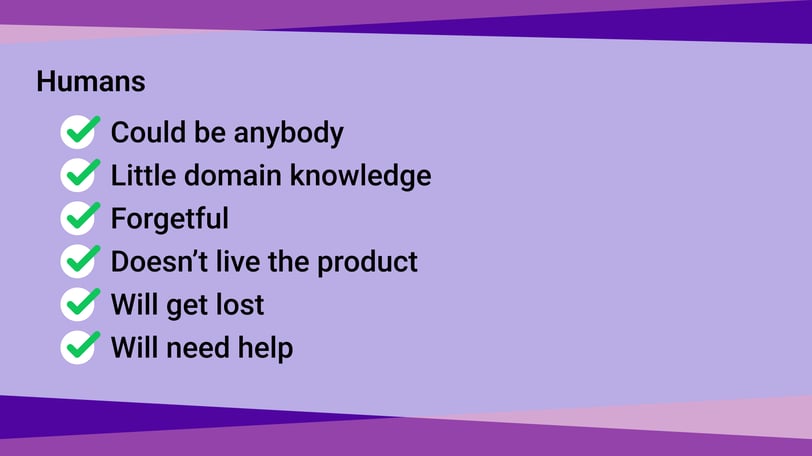

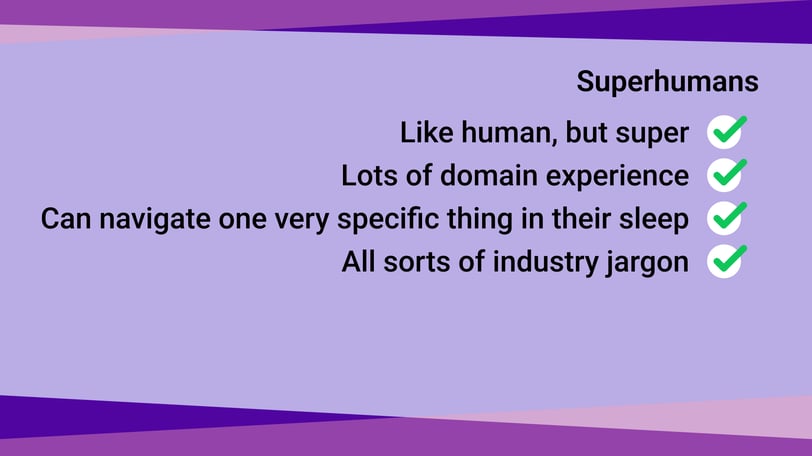

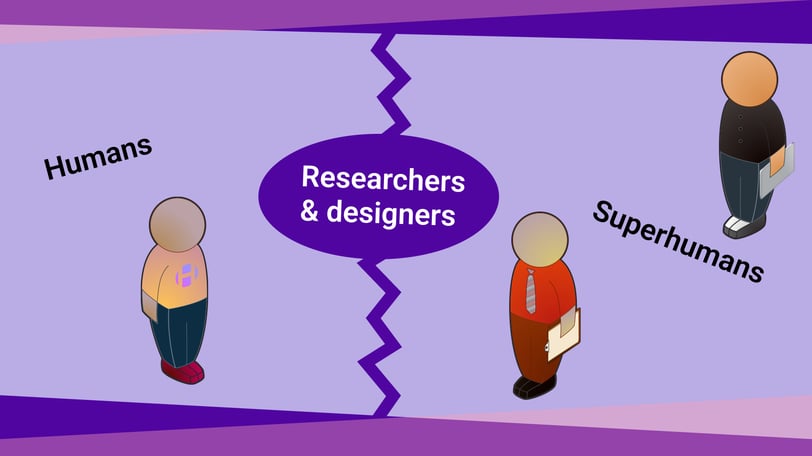

So when I explain to someone on my team that a human won’t be able to use something they’ve thrown together, I’m not saying that engineer isn’t human. It’s that they’re superhuman, and as such, they likely have a hard time understanding the knowledge, expectations, and behaviors of normal humans.

And nobody’s just one or the other. Everyone is human in most areas of life, and superhuman in a select few. You could say I’m more in the superhuman camp when it comes to interactivity, game design, the English language, yo-yo tricks, and hair products. But I’m your typical run-of-the-mill human the second someone brings up C++, agriculture, sailboats, cooking, electricity, contact sports, finances, and any language that isn’t English. So context is pretty important here.

As product designers, information architects, interface geeks and usability nerds (I’m assuming you fit into at least one of those areas), we fall on the superhuman side of things, but it’s also our unique job to understand and accommodate the humans, the normal humans, who will ultimately be interacting with everything our teams create. We’re the bridge between these two groups of people.

Now, while I don’t condone letting your users design your product (that’s an easy trap to fall into, and it happens to the best of us), it is important to find out how humans discuss your product, or at least how they discuss the space your product is in. I like having casual conversations with users, nothing fancy, to see how they think about what’s happening when they go through their tasks. Through this simple exercise, you can catch words they use that your team might not use themselves.

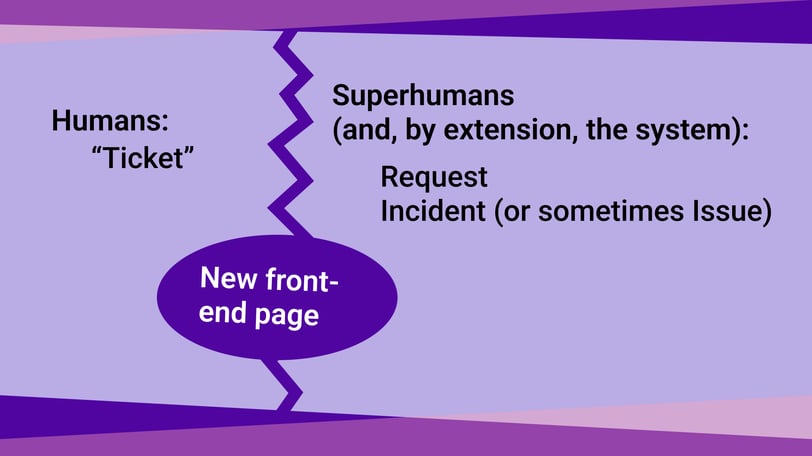

A while ago, I was working on a tech support dashboard for very non-technical humans. This dashboard separated support tickets in Requests and Incidents, so if anyone needed something, the very first step required them to choose one of these options. If they chose the wrong one, they could spend a couple minutes filling out the resulting form before realizing they’d made a mistake. Then they’d have to go back, choose the other option, and start all over again.

Almost everything in the previous paragraph was accurate, except one phrase: “they’d made a mistake.” I hate having to say that, but that’s the assumption of the superhumans who designed the system to include two different but very similar options. The mistake is very clearly on the system’s side, but you wouldn’t know that if you never talked to the humans who had to use the system. Because those humans never used the terms “Request” or “Incident” when reflecting on their tech support journey. They always called them tickets.

The concept of a support ticket isn’t a new thing at all. And 100% of the time, unless we were looking directly at a page with “Request” or “Incident” in the header, everyone used that word. Why were we trying to force them to go against what came naturally to them?

After a couple scenarios, prototyping and usability testing, I was able to convince my team, who’d only known a world of Requests and Incidents, to consolidate those two concepts onto a single page, called Tickets. Unfortunately for the team, in the back end, the framework would still always refer to Requests and Incidents (sometimes called “Issues” for some reason), but now we were able to bridge the gap between human expectation and superhuman-crafted reality.

Here are the takeaways I listed at the end of my CHIFOO talk:

It isn’t easy (and it’s rarely a good idea) to change how the public talks about your product.

The earlier you learn the correct human vocabulary, the easier it’ll be to work those words into the product, in both the front and back end. You want to avoid having to translate superhuman jargon into human vernacular as much as possible.

Your users might not be the end users you need to be listening to. If necessary, find the people who use things made by the people who use your product.

You’re not taking design decisions from anyone during this research. This is just helping you and your team get on the same page regarding language.

Once you know the correct human terminology, get the team using it as soon as possible! If there’s pushback from some team members, remind them that every disconnect between the product team and the users is a possible struggle between expectation and reality.

It’s imperative to any human-navigable system that we understand how humans think and talk about what’s going on in that system, and the earlier the better, because using the wrong terminology in your code will lead to having to constantly translate back-end to front-end language at best, and leaving it how it is because someone on the team’s decided it’s too much effort to make it human-friendly at worst.

Luckily, all that really takes is a casual chat with a few normal humans.